by Darren J. Doherty

2016 marked 40 years since Earl Butz (1909-2008) resigned as USA Secretary of Agriculture, however his vision for ‘getting big or getting out’ and ‘planting fence row to fence row’ has continued unabated — as have the terms of trade decline for producers and the decreased lifespan and increased weight of the commercial broiler chicken.

Last year during one of the #REX‘s I put forward the possibility of returning to natural breeding programs for smaller-scale poultry production — this was in response to our concerns around what we call the #DirtyLittleSecrets of the poultry game — especially as relates to ‘remote’ breeding and all that goes on there. It also relates to the ongoing issue that a number of our poultry-producing clients (and network) have around the sustainability of their enterprises — and more immediately their resilience against disease, feed company & breeder seedstock supply plus ever-increasing public awareness and the questions raised as a result.

What’s the cause and effect here? The cause goes back to chickens being really great feed converters as compared to domesticated ungulates + that chicken tastes really good — hence their historically being seen as ‘special’. The special thing is really that chickens are omnivores and so whilst they are more efficient as food quantity converters that feed has a higher quality requirement to that of herbivores. What’s also special is the volume of cheap fossil energy that is embodied in these organisms. Especially where anhydrous ammonia and urea are used to fertilise the crops that feed the organisms. If it takes around 1000m3 of natural gas to produce 711kg of ammonia then the average US corn crop uses the equivalent of between 2000 and 5000 x 9kg bottles of natural gas per hectare per crop!

Sources: Stratco.com & Bayer.com

“…the purpose of the city is to keep people out of the country…” pers.comm, Bill Mollison (1995)

In the post-Butz era the only omnivore that has not increased in its production volume in the agricultural landscape is Homo sapiens — whilst Sus scrofa (pig) and Gallus gallus (chicken) have both increased in there production exponentially. The big question is how long can chicken (and pork) remain cheap. As human populations increase how much longer can the production from arable landscapes be diverted through omnivorous livestock (and grain-fed herbivores) and not directly to humans?

These are all very heady questions and for people in the world for whom chicken (and pork) is an affordable meat there is an energetic inevitability to these questions effecting the price.

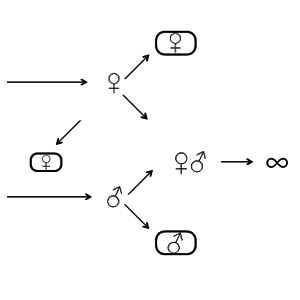

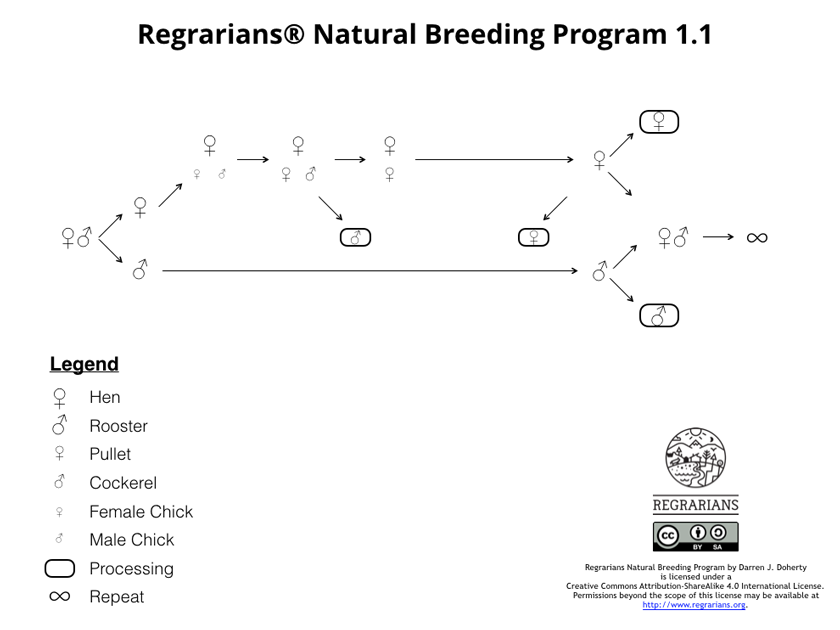

So what does this have to do with the chicken production strategy we’re investigating here? Right now we have producers who have discussed with us many of the aforementioned concerns around their operational sustainability and resilience. We’re looking to trial a strategy that is modelled after what we do with most other livestock. As we would with a boar, bull or ram, we’d have the roosters joined with the hens. The roosters are removed and the hens brood their eggs. The unsexed chicks are raised with the hens and the cockerels are sexed and removed for selection as broilers or as breeding stock. The naturally slower growing pullets remain the hens until they too are selected either as replacements or to be broilers too.

Source: Regrarians® Ltd.

My supposition is that this system would increase the foraging efficiency of the flock considerably as any animal that is naturally raised by its mother is going to be a more voracious forager than an orphan with a feeder as its primary option. Its also likely to be more resilient. Pit a week old chick raised in this way versus a week old orphan with its only guide a flock of other orphans in a field full of forages and its pretty clear which one would survive better — actually survive…

Source: Wikipedia.org

The kind of work we’re looking to trial with the chicken (and ducks for that matter) can’t be done without paying attention to the environment that they are raised in as well. Therein lays another challenge for the omnivore — how to raise a commercially viable flock or sounder and decrease the volume of feed coming from outside the property whilst maintaining condition, breeding and growth rates. Some are using waste streams to varying effect and this is great if it works, but its often transporting water as much as the feed itself. We’re looking at establishing a range of perennial trees, shrubs and herbaceous forages, including self-seeding annuals. The species are going to have to be broad and the timing of delivery is going to have to be wide. The yields of chicken (and ducks and pigs) is going to be lower, the price per unit will be higher, the quality probably higher, the life length longer, the quality of life higher and the energy invested per unit will be lower. Integration in with other livestock, particularly herbivores in a ‘leader-follower’ regime of planned grazing, would be necessary and this would provide a number of passive and active yields — as many people already experience when following the increasingly popular ‘Polyface Farm’ methods espoused by the Salatin family.

People like Reginaldo Haslett-Marroquin (Main Street Project) and Richard Perkins (Ridgedale Permaculture) are doing some great work with increasing the volume of forages produced on-site. Michael Sommerlad is also doing excellent work at the breeding end with his ‘Sommerlad’ breed of chicken. However, in my opinion and experience, they all share a weak link when we look at the true cause of why chickens and ducks are poor foragers and that comes with their not being raised naturally as many other livestock are.

What I’m proposing here is that work of people like Johann Zeitsman being done with cattle adaptability and performance be adapted to other livestock — and in this case chickens and ducks. If an animal ultimately needs to be propped up by distant breeding facilities, lamps, natural gas, fields of other farmers far away, feed hauling, vaccines, and other amendments then what kind of resilience are we building — furthermore what kind of animals are we producing. Are we honestly happy to produce commercial chicken breeds that have a very sketchy backstory and genetic progression? Scratch the rather tragic trajectory of the commercial broiler breeds a little and its certainly not in keeping with the ‘beyond organic’ and regenerative narratives that many so-labelled producers project.

Source: The Wall Street Journal

Where is the work on regionally-adapted chicken (and other livestock and horticultural crops for that matter)? Certainly in the herbivore space there’s been a bit of work but most breeds have origins whose names are not the same as where they are now. That’s a big project and many would argue (and quite correctly) that the hard work’s been done and now its a matter of selecting for positive traits as opposed to mutations.

At first glance what we’re proposing is not going to replace the current model in terms of volume — it has no ambition to do so — it would be an energetic nonsense to even contemplate doing so. Will the labour units per animal produced go up? Absolutely. Would the cost go up per animal produced? Absolutely. Would the energy embedded in each animal increase? Probably. Would these ratios of input:output stabilise over time? Most likely.

Innovation be it social, ecological or financial can be very expensive — accordingly this kind of work is not going to suit the contexts of many who are reading this — that’s what Holistic Management® ‘Testing Decisions’ are there for. However without the innovators and the practices they project, test, fail and succeed at we’ll never know. And with that a few of us will see how we go and let you all know…

Thanks all,

I appreciate the comments that many have brought forward both publicly and privately. As is our policy at Regrarians, we prefer to have public discourse following our public articles and so we won’t be drawn into private conversations around this article — I just don’t have the time to do so PLUS in my opinion these are discussions that peers should be having in the open and without fear or favour. As an avid student of agricultural history I know only too well that modern poultry husbandry (and especially science) is still relatively novel and that commercial ‘pasture-raised’ husbandry and science is even more novel. So I am not prepared to have private conversations in a space that is clearly way too early on the innovation spectra — asides we don’t see the value to anyone in anything less than a completely transparent conversation — some may naturally disagree as is their prerogative and right.

From the outset I made the clear point that its an energetic reality that any omnivore is going to need have its feed requirements augmented in order for production numbers to be sufficient to meet the demands of a western commercial enterprise. I just wanted to reiterate this point before I head into the ‘meat’ of my response.

I obviously raised a number of questions in this article and also didn’t give a lot of answers either. I have concerns around the resilience of our clients’ omnivore operations and the common thread of questioning I have from them is how to provide more feed on-site. To be clear this is a global question not just an Australian one. Also to how do they regionalise breeding and reduce the reliance/dependence on professional breeders — this is especially the case for our clients in places like Maui (Hawai’i USA) where structural dependencies on off-island suppliers of feed and replacements are a primary resilience risk.

On the feed front we’re looking to both short term and longer-term strategies for this. Shorter term is multi-species cover cropping and pasture cropping, ideally where the feed mixes currently bought are cultivated on site in order to ‘mop up’ nutrients and the crops are stripped and siloed or left standing for trampling by herbivores and cleaned up by omnivores. The former offers more control but requires more machinery and infrastructure — the latter is more prone to wastage and potentially to phytotoxins, plus the phenology of the delivery of feed is seasonal at best. As many of you would be aware, we’re actively working to develop equipment to support this process — people no less than Colin Seis now endorsing our most recent iteration (#KeylineSuperPlowMk3) as ideal for organic/conventional farmers wanting to do cover cropping/pasture cropping. This equipment will ultimately be able to be animal powered such that our clients, particularly in the USA (esp. in Essex Co NY) will be able to continue to regenerate their sites whilst growing cereals for both human and omnivore consumption.

On the longer term front the challenges are largely phenological. The ‘Permaculture’ camp have for a long time put forward the concept of mixed species ‘food forest’ as being the way to go. This approach would mimic the conditions those little jungle fowl find themselves in — I know this system very well, having worked in the jungles of Bình Phước province Việt Nam from 2004-2007 and observed daily the habits of these incredibly flighty and well-adapted creatures, whilst also witnessing the management of domesticated chickens (i.e. ‘improved’ breeds) at the many small-holders farms surrounding our project site. In places like Mallorca, Bermuda and Maui (where I’ve lived and worked for extended periods) I’ve also been able to see endemised chickens at work. Their common characteristic is incredible flightiness, varying levels of ‘regression’ back to the phenotypical traits of their wild ancestors and (obviously) high foraging capabilities. Only in Mallorca did I see less of a size decrease than I did in the tropical locations I mentioned. I surmised that this was due to the abundance of energy & protein-rich seeds from various leguminous trees and cereal cultivation. Believe it or not, when we stayed for a month at a villa in southeastern Mallorca in 2014 I hunted these chickens with a very slow slug gun — our host was very tired of these abundant fowl destroying her kitchen gardens and so I got to work as a bit of time out from writing. Hunting chickens with the eye of an ecologist made for very interesting viewing. The majority of these fowl had interestingly maintained very good condition and their weights were quite reasonable — there was no apparent issue with their fecundity either and judging by the number and age-classes of flocks they were breeding year-round. It would be a very interesting study to set someone to…

So back to perennials (!!) — the other approach that I’ve been looking at is where we don’t have so much of a mixed species food forest system (as the more ‘subsistance’ oriented Permaculturalist might promote) but where we have alleys of forage producing shrubs and trees, placed according to the timing of drop and their feed composition. This is proving to be no easy task. The phenology of the ‘drop’ is one thing and that’s the easier of the two primary tasks — composing species complexes so as to provide the majority of the feed needs AND to do so whilst not compromising animal health and performance AND to do so commercially is a considerable design challenge — plus the R&D period is quite extended. Milking Yard Farm’s shelter belt of Quercus sp. (oaks), Acacia sp. and Cytisus palmensis (tagasaste) is somewhat instructive on that level, and there are ample resources from RIRDC (e.g.) to help us determine what Acacia’s might provide seed of value and over what period. Similarly there are a whole range of tree and shrub crops which, in both the temperates and tropical climates, can supply a significant quantity of poultry forage — its the assembly matrix so that we match numbers to space that is the biggest challenge, at least for me…

These systems should also be of concern to any omnivore producer who is liable to being charged with being intensive. This is a discussion I wrote about a couple of years back in my article, “Extensivising Intensive”. As I pointed out, I support the point of intensive farming classifications, as apart from anything else, they’re there to protect the environment from pollution.

With regards to natural raising and foraging characteristics — I cannot see how an orphan with a tray of feed in front of it from day one will forage better than an individual raised by its mother will. You can certainly select for ‘active foraging behaviour’ however the intrinsic functions of orphans remain. Its no different with humans, cows, sheep, ducks or any other species. On the herbivore front the great work of Kathy Voth shows us only too well how our diminution of diversity within pastoral environments has reduced the foraging behaviours of cattle to the point where they have to be shown what they can actually eat — and who ultimately passes on that knowledge — the cow to her calf…Humans are no different and in my observations and experience so are chickens — especially meat breeds, as their life, even when slower grown, is simply too short.

The feasibility of the more natural rearing model is obviously a question that many would point to. I questioned this (and other) points in the article. My opening reference to Sec. Earl Butz’s policy legacy (I’ll throw Norman Borlaug’s legacy in that basket too) that’s made all food comparatively cheap has built a community expectation that poultry products should be cheap. This is of course made possible by the concomitant subsidy of cheap fossil energy — the energy source (s) that supports the bulk of the production and value chain and allows it to be as cheap as it is. This is clearly a moment in the sun as cheap fossil energy is not going to be around forever — and so neither will cheap food. Can we leverage the use of this fossil energy better? I think so, certainly when we look at methods such as mixed species cover and pasture crops.

Obviously labour is another cost, no more than here in Australia where we have very high labour costs and comparatively low supplies of agricultural labour — our commonwealth was constituted too well for that! I do look at the work of luminary farmers such as the late George Henderson who, before the advent of day-old sexing of chickens, was producing chickens in a way similar to what I’d put forward. The innovation of day-old sexing took the work of hatching out of the hands of the poultry farmer and was one of the measures that led to the vertically integrated systems of today. Labour is a significant cost and how many units of labour (and energy) are we prepared to put into producing an omnivore is considerable — again its that trophic reality that one can’t escape. So yes under this model chicken would become more expensive than it is right now. What’s the true energy cost though? My guess is that the chicken/omnivore produced in this model would have a smaller energy cost than any of the commercial systems used, especially were we to ‘nail’ the aforementioned annual/perennial-based forage systems.

In closing I know that we will have clients who will take up some of these challenges and we’ll work closely with them in doing so. Like any pioneering innovators this will come at a cost and will not be for everyone. That’s why we recommend the Holistic Management methodology and its ‘Holistic Context’ practice — determine what’s important to you and how that fits with your financial, ecological and social contexts. As I continue to hammer home with our clients, innovation is expensive…However not having innovations on this front will continue dependancies which may not always be resilient…